Posted by

Marisa Armeli

Posted by

Marisa Armeli

Posted by

Marisa Armeli

Posted by

Marisa Armeli

📚 The Pen and the Patriarchy: Female Writers as Critics of Civilization

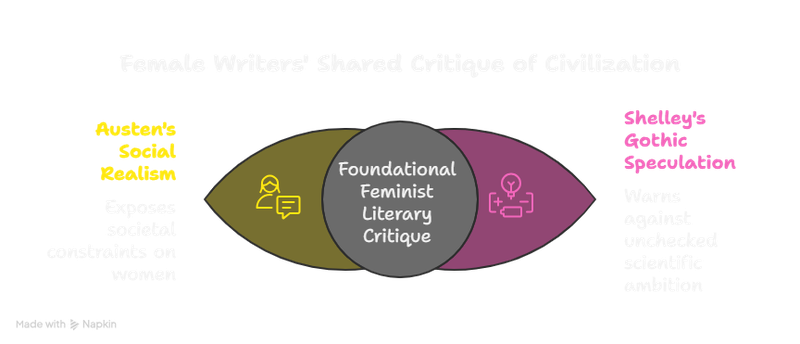

Jane Austen and Mary Shelley, separated by genre yet united by their unique vantage point as women writing at the dawn of the 19th century, offer contrasting yet complementary critiques of "Civilization". Their novels, Pride and Prejudice (1813) and Frankenstein (1818), establish the female writer not merely as a storyteller, but as a trenchant diagnostician of society’s profound limitations and intellectual dangers.

Two Civilizations, Two Critiques

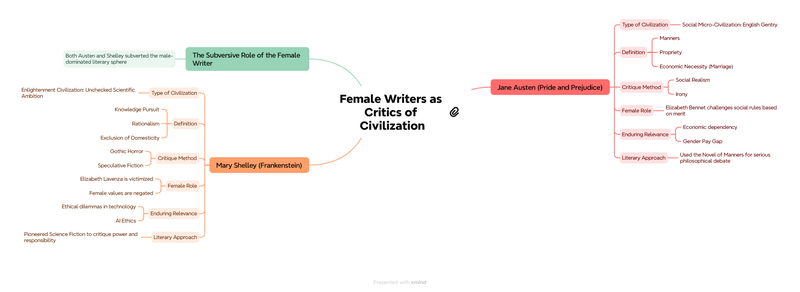

Austen's world in Pride and Prejudice is a micro-civilization—a tightly regulated society of the English gentry where marriage is the primary economic and social transaction for women. Her civilization is defined by manners, propriety, and the financial necessity dictated by legal structures like entailment (as seen with the Longbourn estate). Austen’s critique is delivered through social realism and irony: she holds up a mirror to a society that values superficial accomplishments and inherited wealth over genuine intelligence and emotional honesty, trapping women like Mrs. Bennet and her daughters in a frantic search for security. Her heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, achieves fulfillment not by rejecting civilization entirely, but by demanding a position within it based on mutual respect and true merit, forcing Mr. Darcy to reform his proud, class-based prejudices.

In sharp contrast, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein attacks the grander, more abstract Enlightenment Civilization built on scientific ambition and rationalist pursuit of knowledge. Shelley, the daughter of the radical philosopher William Godwin and feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft, uses Gothic horror and speculative fiction to issue a profound moral warning. Victor Frankenstein's failure is his complete rejection of domesticity and social responsibility—the traditional female sphere—in favour of a solitary, masculine quest to "pioneer a new way" and usurp nature's reproductive role. The creature's subsequent abandonment and descent into violent rage symbolize the catastrophic consequences of a civilization that prioritizes unchecked scientific progress over compassion, empathy, and community. Women in Frankenstein—like Elizabeth Lavenza and Justine Moritz—are consistently victimized, marginalized, or destroyed, highlighting how male ambition eliminates the very social fabric that gives life and ethics meaning.

The Role of the Female Writer

As female authors, Austen and Shelley utilized their genres to subvert the male-dominated literary landscape. Austen employed the novel of manners, a genre often dismissed as "feminine," to conduct serious philosophical debates on ethics, class, and marriage. By writing anonymously, or "By a Lady," she created a space where her sharp wit could dismantle patriarchal structures without inviting the personal censure often aimed at female intellectuals.

Shelley, by writing an origin story for modern science fiction, ventured into a traditionally masculine realm of thought. Her position on the margins of society (as a non-married mother and intellectual partner to Percy Shelley) gave her a clear view of the dangers inherent in systems that exclude the female perspective. Her novel suggests that the failure of Victor's scientific "civilization" stems precisely from its exclusion of feminine values—care, responsibility, and connection.

Connecting to Contemporary Thought

The dialogue started by these two writers continues today, solidifying their role as proto-feminist literary ancestors. Contemporary female writers—such as the Nobel laureate Toni Morrison or the author of The Handmaid's Tale, Margaret Atwood—continue to use literature to scrutinize civilization, directly addressing the enduring issues of power, identity, and the female body.

Austen’s analysis of economic dependency resonates with modern discussions of the gender pay gap and the struggle for women's professional autonomy. Shelley's warning against dehumanizing technological progress and the failure of creators to care for their creations is directly relevant to contemporary debates on Artificial Intelligence ethics, genetic engineering, and environmental responsibility. Both authors, through their distinct narratives, established the foundational truth that the health of any civilization cannot be measured solely by its wealth or scientific achievement, but by the dignity and inclusion it affords its most vulnerable members—a message that remains vital for the 21st-century female writer.

Posted by

Marisa Armeli

Posted by

Marisa Armeli